Pétrus Ký (1837-1898) in 1883, aged 46

In 1885, scholar Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký delivered a lecture at the Collège des Interprètes entitled Souvenirs historiques sur Saïgon et ses environs (Historical Memories of Saigon and its Environs). Published as a booklet later that same year, it provides us with one of the most important historical accounts of Saigon-Chợ Lớn in the pre-colonial period. The text has been translated into English and this is part one – the rest will be serialised here over the next few weeks.

Gentlemen,

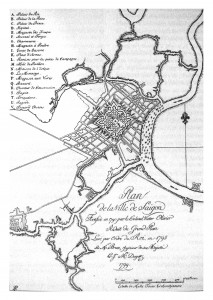

The city of Saigon has undergone a complete transformation since the day when the French flag replaced the yellow Annamite [Vietnamese] flag in this country. This change began in 1859, taking place gradually but unceasingly, and it is to this that we owe the pleasant appearance with which the capital of Lower Cochinchina now presents itself.

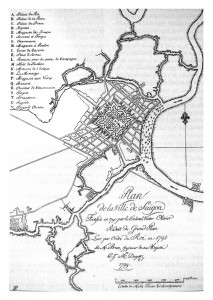

Saigon in 1795

Today I want to trace a tableau of both old and modern Saigon, bringing the two descriptions together in such a manner as to compare and contrast the differences between the states of civilisation in two epoques separated by just a quarter of a century.

One hopes to preserve the memory of a place, especially when it was the scene of so many events that have occurred in such a short space of time, each obliterating traces of the other.

Historical traces are the links that tie together the epoques of nations, and often of states which have disappeared into oblivion. Factual memory weakens in proportion to the number of successive generations. These continuous changes are a necessary condition of the life of things and of peoples, but the memory of them would be altered if history did not set them down in writing at times, in order to preserve their character.

This Saigon which we regard with indifference today has witnessed events that excite our curiosity, because they have not yet entered the domain of history, but in future they will arouse passionate interest from our successors. Therefore, let us take a walk through old Saigon, let’s visit all of its parts and make an account of our observations, both geographical and historical.

So what was Saigon like in times gone by? Before and during the reign of Gia Long? During the reigns of Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị and Tự Đức? And what was its appearance at the time of the arrival of the French?

The name “Saigon”

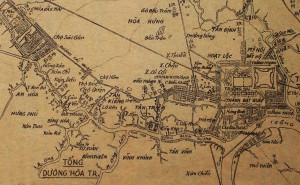

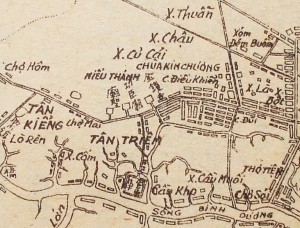

This 1815 map shows the “Saigon Market” in what is now Chô Lớn

Before describing the ancient citadel, it’s first necessary to find out where the name we give our city originated.

Saigon was originally the name given to the current Chinese city. According to the author of the Gia Định thông chí (Description of Lower Cochinchina), Sài was a borrowed word in Chinese characters meaning “wood,” while Gòn was the Annamite name for cotton and the cotton plant. The name comes, it is said, from the amount of the cotton that Cambodians planted around their ancient earthworks, whose traces still remain at the Cây May Pagoda and surrounding areas.

To us, it seems that the name can only be that which the Cambodians gave to this country and which was later applied to the city. However, I have still not yet been able to ascertain its true origin.

The city of Saigon was so called by the French, who found the name on European maps of bygone days, which designated the city under this general but vulgar denomination, sometimes used to describe to the entire province of Gia Định.

Saigon before Gia Long

Saigon before Gia Long was, it seems, little more than a simple Cambodian village. However, in 1680 it was, for a certain time, the residence of the second king of Cambodia.

According to history, the country was invaded peacefully by Annamites under the leadership of the government of Huế in 1658, during the reign of Nguyễn Phúc Tần, lord of the south.

The countryside around Saigon

After having conquered the territory of Champa (Chiêm Thành) by driving back its former inhabitants, the Annamites found themselves neighbours of the Cambodians (Khmer people), whose mind had been influenced by the success of the Annamites (“children of the celestial king”). The settlement soon became much larger following settlement by Chinese supporters of the Ming dynasty, which was permitted and encouraged by the court of Huế.

In 1680, two senior commanders of the Ming troops, preferring to serve the Annamites than to submit to the Qing, the Manchu Tartars who were the new conquerors of China, came in 60 junks to Tourane, followed by 3,000 soldiers, with the aim of establishing themselves there. They sent a request to this end to the lord of Huế. The King of Annam, after treating them to a banquet, gave them a letter to show to the King of Cambodia, asking permission for them to settle in Cochinchina and exploit its vast wastelands. Arriving at Đồng Nai, they divided into two groups; one settled in Biên Hòa, while the other headed for Mỹ Tho.

One of the two kings of Cambodia lived at Gô-bich, while the second king lived in Saigon. The latter, finding himself threatened on one side by the Chinese of Mỹ Tho and on the other by those of Biên Hòa, wrote to the king of Huế asking him to intervene to prevent the intrigues of his protégés.

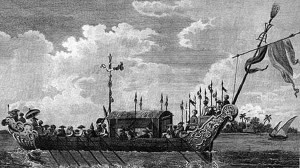

Boats on the Saigon River

The king of Huế set himself up as the arbiter of this dispute and undertook to resolve it. For this purpose, he sent General Văn in an expedition against the Chinese and against the king of Gô-bich, who took refuge in strong fortresses, barricaded the Mekong River with iron chains, and thus impeded trade with the Annamites.

After having defeated the Chinese at Mỹ Tho, this general moved forward to Gô-bich. The first king, Néâch-ông-thu, then retired to Oudong and finally concluded a treaty with the Annamite general, who left Cambodia and returned to Bến Nghé (Saigon)

One year later (1684), Néâch-ông-thu was unfaithful to the execution of the treaty. Nguyễn Phúc Tần (King of Huế) sent Nguyễn Hữu Hào to declare war on him. The king of Cambodia was taken prisoner, and soon after arriving in Saigon he was taken ill. The second king, then resident in Saigon, killed himself.

His son, Néâch-ông-yêm, was placed on the throne and installed at Gô-bich by the Annamites.

The intervention of the court of Huế led to immigration by Annamite settlers, who, encouraged by the government, gradually occupied the country. This permitted Lord Nguyễn Phúc Chu in 1698 to establish prefectures, sub-prefectures, townships and villages and to create, for this country, an administration similar to that of the rest of the kingdom of Annam. First Biên Hòa and Gia Định formed themselves into a phủ [prefecture], subdivided into two huyện [districts]. From this came the name người hai huyện (people of the two districts), to describe the residents of Biên Hòa and Gia Định.

A late 18th-century Nguyễn dynasty warship

In 1772, the Tây Sơn (montagnards of the west), Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Lữ and Nguyễn Huệ, revolted against Huế; and at the same time, the Trịnh (Trịnh Sâm) came to attack the city of Huế. Lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần and his nephews Nguyễn Phúc Đồng and Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (later King Gia Long) took refuge in 1774 in Gia Định (Đồng Nai), Saigon.

For 15 years, Gia Long was chased and hunted by the Tây Sơn. He returned from time to time to Saigon, but stayed there very little and was driven out by his enemies who, from Qui Nhơn, constantly returned to the offensive.

Saigon under Gia Long

It was in 1789 that Gia Long, after taking over the city of Saigon which had previously been occupied by the Tây Sơn, built the first citadel, and I will indicate the former location and traces of this in relation to the territory of modern Saigon. In 1788, Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran, apostolic vicar in Cochinchina, who took Gia Long’s son Prince Cảnh with him to France to ask for help, returned to Saigon with French officers. By this time, Gia Long had already retaken Saigon and established himself there.

The following year, Gia Long built the ancient citadel of Saigon, under the direction of Monsieur Ollivier, engineering officer.

A 1795 map showing the location of the 1790 Gia Định Citadel

It took the approximate form of an octagon (a shape insisted upon by Gia Long himself) with eight gates, following the shape of the Bát quái [bāguà 八卦, the eight trigrams used in Taoist cosmology] and representing the four cardinal points with their subdivisions.

The citadel, including its moats and bridges, was built of large Biên Hòa stones. The height of the wall was 15 Annamite cubits (5.20m).

The centre, where the flag tower stood, was located approximately in the vicinity of the present cathedral. From its summit, one could see very far into the distance. It extended: from south to north along modern rue Mac-Mahon [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa] up to the wall of the later [1837] citadel, which was destroyed by the French, and from east to west from rue d’Espagne [Lê Thánh Tôn] to the rue des Moïs [Nguyễn Đình Chiểu].

To the east were the two front gates (cửa tiền). The one called the Gia Định Môn overlooked the square and the Canal du marché de Saigon [Nguyễn Huệ boulevard]; the other, Phiên An Môn, was in the vicinity of the Naval Artillery, on a street which ran along the canal de Kinh Cây Cám.

The rear wall to the west also had two gates: the Vọng Thuyết Môn and the Củng Thần Môn, facing in the direction of the second and third arroyo de l’Avalanche bridges [Bông and Kiệu bridges over the Thị Nghè creek].

The left side of the citadel looked north, with two gates: the Hoài Lai Môn and the Phục Viễn Môn, overlooking the first arroyo de l’Avalanche bridge [Thị Nghè bridge].

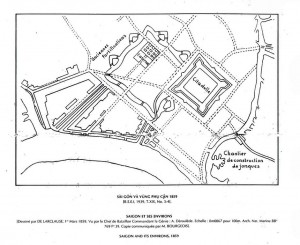

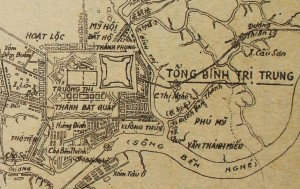

An 1859 map of Saigon showing the locations of both the 1790 and 1837 citadels

The right side of the citadel had the Tĩnh Biên Môn and the Tuyên Hóa Môn gates, located on rue Mac-Mahon [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa]; one opened onto the route Stratégique [Điện Biên Phủ], and the other onto the route Haute de Chợ Lớn [Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, Trần Phú].

The Gia Định Citadel was occupied by Gia Long for 22 years, during which time he went every year in expedition against the Tây Sơn, in seasons when the monsoon was favourable.

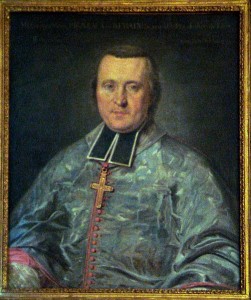

The funeral of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine

As the funeral of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine took place in Saigon at this time, we will digress for a moment to attend the ceremony in which both religion and royalty were impressively represented.

After his return from France, the Bishop of Adran lived in Saigon, in a house that Gia Long had built for him on the outer corner of the Citadel, at the location where the gunpowder magazine is located, called the Dinh Tân Xá [Tân Xá Palace]. The Christians of Thị Nghè had their church close by, on the edge of the creek, and this formed part of the parish of Tân Sơn where the tomb of the bishop is located now.

The Monsignor had built a country house there, where he would occasionally relax with his pupil, Crown Prince Cảnh.

Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau, Bishop of Adran (1741-1799)

Prince Cảnh was sent to the siege of Qui Nhơn. At the urging of Gia Long, the Bishop accompanied him to serve as his mentor. But after 33 years of a very rough and laborious life, Pigneau was attacked by acute dysentery.

Gia Long, driven by a genuine affection for the prelate who had rendered him the most eminent services, sent his best doctors and used every possible means to preserve his life. Prince Cảnh came every day to visit his tutor, and Gia Long himself came several times to see his benefactor, despite his preoccupation with the siege of Qui Nhơn, from which he tore himself away out of a sense of gratitude.

On 9 October 1799, the bishop died in the arms of Monsieur Lelabousse, the missionary who had accompanied him; he was 58 years old. Gia Long, having received the sad news of the death of his illustrious guest, sent a beautiful coffin along with silk to wrap the body. On 10 September, his body was placed on one of the king’s ships for the return to Saigon, where he was to be buried.

Arriving in Saigon on 16 October, his body was placed in the episcopal palace, where it remained on view for two months.

Prince Cảnh, who had accompanied the body of his tutor, considered himself a disciple and eldest son of his master the prelate, for whom he was in deep mourning. He had a special temporary palace built opposite the bishop’s house, and stayed there day and night, receiving many mandarins who came from all parts of the kingdom to render illustrious funeral honours to the deceased.

Gia Long finally returned from Qui Nhơn. To show his gratitude to the prelate, he presided in person at the funeral ceremony. The funeral took place on 16 December 1799 at Tân Sơn, about 5km from Saigon.

King Gia Long (1762-1820), born Nguyễn Phúc Ánh

Prince Cảnh was responsible for leading the procession, which set off at around 2am.

A large cross, formed from artfully-arranged lanterns, was carried at the head of the procession, followed by a series of elaborately carved red and gold portable shrines, each held aloft on an ornate dais and carried by four men.

In the first were four characters of gold, 皇天主宰, Huáng tiān zhǔ zǎi or Hoàng thiên chúa tể, meaning “Sovereign Lord of Heaven;” in the second was an image of St Paul; and in the third an image of St Peter, patron of the Bishop of Adran. The fourth contained an image of the guardian angel and the fifth an image of the Blessed Virgin.

Then came a great standard measuring some 15 feet in length and made from damask, on which were embroidered in gold letters the titles conferred on the Bishop of Adran by the Kings of France and of Cochinchina, as well as those of his episcopal office. After this came a litter housing the insignia of the prelate, his cross and his mitre, which was carried directly in front of the hearse. On either side of these shrines and litters walked a large number of Christian young people and clergy from every church in Cochinchina.

The hearse carrying the body of the Bishop was a beautiful litter of about 20 feet in length, carried by 80 picked men, and covered by an embroidered gold canopy. On it was placed the magnificent coffin, covered with beautiful damask, set in a frame and surrounded by 25 large lit candles.

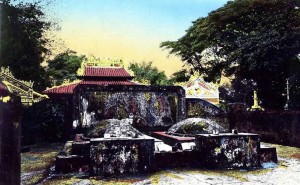

An 1869 photograph of the Pigneau de Béhaine Tomb, commissioned by Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in 1799

The King’s royal guard, comprising more than 12,000 men, was arranged in two lines, with field guns at the head of each line. One hundred and twenty war elephants with their escorts and mahouts walked on both sides. Drums, trumpets and both Annamite and Cambodian military music accompanied the mournful march, which was lit by a prodigious number of candles and torches and more than 2,000 lanterns of different shapes. At least 40,000 men, both Christians and pagans, followed the convoy.

Gia Long was present, along with his mother, his sister, his queen, his children, all the ladies of the court and the mandarins of different government departments. All wanted to express their regret at the eminent and distinguished prelate who was no more, following his remains to the grave which had been prepared to receive him.

Arriving at the grave, the King let a missionary named Father Liot perform the ceremonies of the Catholic liturgy.

The Christian burial ceremony thus completed, Gia Long stepped forward and gave a tearful funeral elegy which he had composed himself. This elegy had been transcribed onto embroidered silk and was presented to the late bishop in the form of a posthumous diploma:

The screen in front of the Pigneau de Béhaine Tomb

“I had a sage, the confidant of my most secret thoughts, who, despite the distance of thousands of miles, came into my kingdom and never left me, even when fortune eluded me.

Why must it be now, at the moment when we are the most united, that this premature and untimely death comes to separate us forever? I talk of Pierre Pigneau, Bishop of Adran, and keeping always in mind the memory of his virtues, I want to give him a new token of my gratitude. I owe it to his rare merits. If in Europe he was known as a man of superior talent, here he was regarded as the most illustrious foreigner ever to appear at the court of Cochinchina.

In my youth, I had the pleasure of meeting this precious friend, whose character fitted so well with mine. When I took my first steps towards the throne of my ancestors, I had him at my side. For me he was a rich treasure, from whom I could draw all the advice I needed to direct me.

But all at once, a thousand misfortunes fell down upon the kingdom, and my feet became as shaky as those of Thieu-khang dynasty of the Ha, so that we had to take a path that separated us as far as heaven from earth. But you, dear master, you embraced our cause with a firm and faithful hand, following the example of four old Hao sages who reinstated the Crown Prince of the Emperor Han-Cao-Te to his rightful status! I confided to you our Crown Prince, when you accepted the mission to go and seek on my behalf the interest of the great monarch who reigned in your country. And you managed to get help for me.

The main shrine inside the Pigneau de Béhaine Tomb

They were already at the half way point when your projects encountered obstacles that prevented them from succeeding. Despite this, you wanted to return to my side, regarding my enemies as yours, to seek the opportunity and the means to combat them. In 1788, when my flag was once more raised over Saigon, I looked forward with impatience to some happy noise announcing your return from France. And in 1790, your boat came floating back onto the waters of Cochinchina. In the skilful and full way of gentleness with which you trained and led the Prince, my son, we saw that heaven had singularly gifted you with the skills of education and youth leadership.

My esteem and affection for you grew day by day. In difficult times, you provided us the means that only you could find. The wisdom of your advice and virtue that shone into the playfulness of your conversation brought us closer and closer, we were such friends and so familiar together that when business called me out of my palace, our horses walked side by side. We never had anything but the same heart.

Since the day when, by happy chance, we met, nothing could alter our friendship, our mutual dedication and boundless confidence that marked our relationship. I hoped that robust health would enable me to continue tasting the sweet fruits of such unity for a long time! But now the dust covers this beautiful tree! What bitter regrets!

To show everyone the great merits of this illustrious foreigner and spread abroad the fragrance of the virtues he always hid under his modesty, I deliver to him the title of Tutor of the Crown Prince, confer on him the dignity and title Quan Công and give him the name Trung Ý. Alas! when the body dies and the soul rises towards the sky, who could keep it chained here? I have finished this short elegy, but my regrets will never end. Oh, beautiful soul of the master! Receive this homage!”

An 1867 image of the Pigneau de Béhaine Tomb, commissioned by Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in 1799

After the funeral oration, the clergy and the Christians withdrew, and the King, alone with the mandarins, offered the customary sacrifices to the spirits of the deceased; afterwards, the King, Prince Cảnh and the ministers each pronounced their own eulogies.

The King had a rich mausoleum built to cover the mortal remains of his faithful guest whose outstanding services he had recognised, and allotted to him a perpetual honour guard of 50 men. This tomb (Cha Cả, as the Annamites call it) survived the persecution [of Catholics and missionaries], protected by the memory of King Gia Long and reverence for the dead, which is one of the virtues of the Annamite people.

After the occupation of the country, France raised the tomb of the most devoted of its children in the Far East to the dignity of a national monument.

Finally in 1814, Gia Long fixed his residence in Huế and was master of all Annam, from Tonkin to Cochinchina. It was Lê Văn Duyệt, the famous conqueror of the port of Thị Nại (Bình Định), who was appointed Governor General of Lower Cochinchina. He lived in Saigon. His official residence was behind the Hoàng Cung (Royal Palace), today Norodom boulevard [Lê Duẩn], almost at the point where the Bishop’s Palace is located. That of his wife was in the Government Palace outside the rampart and the wall of the citadel.

To read Part 2 of this serialisation, click here

To read Part 3 of this serialisation, click here

For other articles relating to Petrus Ky, see:

“A Visit to Petrus-Ky,” from En Indo-Chine 1894-1895

Old Saigon Building of the Week – Petrus Ky Mausoleum and Memorial House, 1937

What Future for Petrus Ky’s Mausoleum and Memorial House?

Part 2

Pétrus Ký (1837-1898) pictured in the 1890s

In 1885, scholar Pétrus Trương Vĩnh Ký delivered a lecture at the Collège des Interprètes entitled Souvenirs historiques sur Saïgon et ses environs (Historical Memories of Saigon and its Environs). Published as a booklet later that same year, it provides us with one of the most important historical accounts of Saigon-Chợ Lớn in the pre-colonial period. This is the second instalment of the serialisation, translated into English.

To read Part 1 of this serialisation, click here

Saigon under the rule of Viceroy Lê Văn Duyệt

Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt (1763-1832)

Now lets look at the reign of the “Great Eunuch,” who lived in the former Saigon until his death. Lê Văn Duyệt, then called Ông Lãn Thượng, ruled the country peacefully under Gia Long and during the first part of the reign of Minh Mạng, although occasionally he made expeditions against the Cambodians when they rose up in revolt.

He was known as the “terror of Cambodians,” a good, fair, firm and even inflexible Annamite administrator. He was plenipotentiary, exercised extraordinary powers and proved an inviolable governor, fearless of death; he had the right to condemn people to death and to execute the sentence without prior recourse to the confirmation of the Royal Ministry of Justice. He only had to make a simple report after the execution was carried out. It was thanks to this power that he succeeded in completely pacifying the country.

Without going into the details of his private or public life, let’s look for a moment at his administrative career.

As he loved combat, he set up a kind of arena where men fought tigers or elephants. He also had a passion for cockfighting and for theatre. These forms of entertainment occupied his leisure time.

Every year, shortly after Tết, he reviewed the troops of the six provinces in Saigon on the Plaine des tombeaux (Đồng Tập Trận), today the area known as the Polygone [the large military training area initially known as the “Polygone d’Artillerie” was later redeveloped as a military barracks and after 1954 this became became “Camp Lê Văn Duyệt,” headquarters of the Third Corps of the Army of the Republic of Việt Nam (ARVN)]. The purpose of this review was both political and religious, or even superstitious. It was intended to show ostentatiously that he was ready to punish all disorders and at the same time to drive away evil spirits. Here’s how this “Ra Binh” ceremony was carried out:

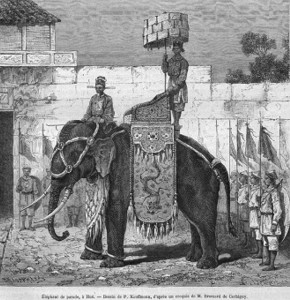

A Nguyễn dynasty elephant parade

On the eve of the 16th day of the first month of the New Year, the Governor, after fasting and abstinence, and in full dress, would pay tribute to the king in his temple. Then, after three shots from the cannon, he mounted a palanquin (sedes gestatoria), which was both preceded and followed by his troops. He went out of the Citadel in procession, either from the Gia Định Môn or the Phiên An Môn gates, headed towards Chà Vải, and along rue Mac-Mahon [modern Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa street] to reach the Mo-sung ceremonial area.

There, cannon shots were fired, troops were manoeuvered and elephants were exercised. The Governor then continued in procession to the Shipyard, where he attended a mock naval combat before returning into the Citadel. During the procession, people made much noise, setting off firecrackers to drive away the evil spirits that may haunt their houses.

On the second Tết, that is to say, in the fifth month, the Governor went to carry out the Tịch Điền (ploughing) ceremony (where the sovereign or his delegate made an example to his people by doing some work himself). The location reserved for this ceremony was almost immediately in front of the Hospital of the Sisters of St-Paul in Thị Nghè.

Saigon during the reign of King Minh Mạng

And so, we come to the reign of Minh Mạng. The Governor General went to Huế on the occasion of Minh Mạng’s accession to the throne. At that time, his comrade-in-arms, Nguyễn Văn Thiêng, was Governor General of Tonkin.

Minh Mạng, King of Cochin-China, from John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China, exhibiting a view of the actual state of these kingdoms (1828)

Minh Mạng, after having stripped his legitimate rivals, began to plot the removal of two glorious veterans whose ongoing actions interfered with the accomplishment of his designs: the Marshal of the central region, then Viceroy of Tonkin, and the “Great Eunuch” Lê Văn Duyệt, who respected the French, and whose presence in Huế interfered with the king’s schemes.

The king proposed to accuse them of rebellion in order to make them disappear. To achieve this, he won over their secretaries and their seal guardians. He began with the Viceroy of Tonkin; a stipendiary strove to imitate the writing of Viceroy Thiêng and his son. A forged letter which had supposedly been intercepted was then brought to Minh Mạng.

It was a general call to arms against the king, the writing imitated that of the son of the Viceroy of Tonkin, and the letter bore the seal of Viceroy Thiêng himself. Minh Mạng immediately recalled Viceroy Thiêng from Tonkin. The proof was clear; Thiêng and his son were ordered to commit suicide. This favour, known as the tam ban triều diện, involved offering the “privileged condemned” a choice out of three possible means of destruction – (i) 3m of pink silk with which to hang or strangle oneself; (ii) a glass of poison to drink, and (iii) a sword with which to cut one’s throat.

Lê Văn Duyệt, seeing his old friend sentenced in front his eyes, a victim of the duplicity of the king, guessed the plot by which he, too, would eventually succumb. By a truly providential presentiment, he left the palace to go home and see if his seal was still in its usual place. Not finding it there, he without delay sought his seal guardian, who was found semi-conscious, next to a well. Searching him, they found on his person the lost seal and a fake letter which had not yet been stamped. The seal guardian was beheaded that same hour, on the orders of the Marshal. He then went to find Minh Mạng, and told him that Lower Cochinchina was the victim of exactions by bandit leaders and that his presence there would put to an end these disorders, which threatened to worsen.

Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt’s tomb, pictured in the French colonial era

Minh Mạng, not daring to keep him there, and happy indeed at his voluntary removal from the court, let him go. Lê Văn Duyệt therefore returned to Saigon as Viceroy, and he arrived in time to suppress an insurrection by the Cambodians of Trà Vinh (1822). He remained in Lower Cochinchina until 1831, the year of his death. He was very fearful of Minh Mạng, who did not, however, dare to move against this loyal and brave soldier, representative of his father, his own guardian and tutor. The greatness of his services had made the Viceroy almost inviolable.

After Lê Văn Duyệt’s death, Minh Mạng, who had kept a deep grudge against him, but had never dared to undertake anything against him during his lifetime, avenged himself basely. He profaned the Marshal’s tomb by encircling it with a chain and whipping the grave tumulus with 100 lashes; this vile, shameful and miserable vengeance was the only revenge he could take against a servant who, along with Gia Long, Thiêng, Võ Tánh, French officers and so many other brave companions, had destroyed the Tây Sơn and reunited the kingdom of Annam. Lê Văn Duyệt’s tomb was eventually restored by Thiệu Trị, son and successor of Minh Mạng. We can see it today, repaired and maintained by the care of the French government, in front of the Inspection de Gia Định.

When Duyệt died, the Bố chánh of Saigon, Bạch Xuân Nguyên, to please Minh Mạng, attacked the Viceroy’s memory, and in his investigation report accused him of wanting to become independent, and in particular of collaborating with Nguyễn Văn Khôi [Lê Văn Khôi, the adopted son of Lê Văn Duyệt] to exploit the forests…

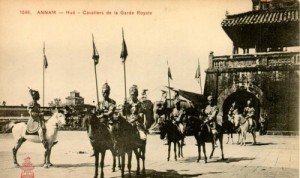

Royal cavalry in Huế during the French colonial era

Nguyễn Văn Khôi was demoted and told to go to Huế to explain. Instead of obeying, he rebelled, along with the principal officers of the late Viceroy Lê Văn Duyệt.

At night time, prisoners were released, and all followed Nguyễn Văn Khôi, who went to cut off the head of the Tông Đốc Nguyễn Văn Quế and that of his accuser, Bố chánh Bạch Xuân Nguyên.

The city of Saigon fell into the hands of Khôi. The next day, proclamations were posted at Mỹ Tho and in the western provinces on the one hand, and in Biên Hòa, Bà Rĩa and Mô Xoài on the other, declaring submission to the chief of the insurgents. Lower Cochinchina was all theirs.

At the news of this insurrection, Minh Mạng sent troops by land and sea. They arrived at about the same time: the first group at a place called Đồng cháy (burned field), and the second in the Saigon River, along the Giồng Ông Tố. The river was blocked by iron chains, between the Fort du Sud and the fort on the opposite bank. The attack began at night on the 6th day of the 7th month; a passage was forced, and by next day, Khôi’s troops had retreated into the Citadel.

Minh Mạng’s fleet anchored in the Saigon River and in the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè Creek]. Ground troops encamped in front of the Citadel. The besiegers then constructed a series of earthen forts around it, each higher than the walls of the Citadel. But the fall of Saigon was delayed by the intervention of the Siamese, who, solicited by Nguyễn Văn Khôi, appeared in Hà Tiên and Châu Đốc, and forced the King of Cambodia to flee from Vĩnh Long. Driven back, the Siamese returned home by fighting their way through Pursat and Battambang.

Father Joseph Marchand was arrested in 1835 in Saigon and martyred by having his flesh pulled by tongs (the “torture of the hundred wounds”)

To monitor and protect against both the Siamese and Cambodians, the Annamite General Trương Minh Giảng ordered the construction of a citadel called An Mari in Phnom Penh and installed himself there (1834). The Siamese left and five provinces fell rapidly to the officers of Minh Mạng. But Saigon, besieged for about a year, still held.

The first assault was made in the 4th month of 1834 for eight hours without success: the attackers were beaten. The Citadel did not finally fall until after repeated assaults (the 6th day of the 7th month). The victory was costly. Vae victis! The day of victory was also one of carnage, we could not count those who were cut down by arms!

The son of Khôi, together with a French missionary named Father Joseph Marchand of the Paris Foreign Missions Society and the captured rebel mandarins, were all placed in cages and taken to Huế, where they perished by slow death. A total of 1,137 men were executed on the Plaine des tombeaux and buried in a mass grave covered with a high mound called Mả Biền tru (tomb of people cruelly killed, mound of terror), or more vulgarly Mả Ngụy (tomb of the rebels).

After the capture of Saigon, Minh Mạng ordered the destruction of the Citadel raised by Monsieur Ollivier, under Gia Long, because it was too large and required too many troops to be well defended. It was replaced by a less extensive work, which was captured by the French in 1859, and on the site of which today stand the new Marine Infantry Barracks.

The villages and canals of old Saigon

Returning to the walls of the ancient Citadel of Saigon, let’s descend first to its front face, that is to say, all the lower part, stretching from the rue d’Espagne [modern Lê Thánh Tôn street] to the banks of the Saigon River.

A 1799 map of Saigon

This area was one of the parts of the former Annamite commercial city, dotted with houses and shops and intersected by narrow, poorly maintained streets which were included in the territory of four villages, from the mouth of the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghé Creek] to that of the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghế creek] – Hoa Mỹ (shipbuilding), Tân Khai, Lũng Diện and Trương Hoa, whose boundary was at rue Mac-Mahon [modern Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa street].

The upper part was part of the village of Mỹ Hội, whose territory included the Citadel. At that time, the mayor of this village was one of the greatest mayors of the city. He was entitled to wear the gourd-shaped cap (Trái bí) and exercised the administrative powers of a district chief.

The village had a đình, or communal house. The king sent, by delegate, on a golden platter, five ligatures and gifts to inaugurate its buildings.

The area called Hàng Đinh (Nail maker’s village) was at the top of rue Catinat [modern Đồng Khởi street], stretching from the Hôtel Laval [aka the Hôtel Fave, forerunner of the Grand Hôtel Continental] to the Hôtel du Directeur de l’Intérieur [at the modern Đồng Khởi-Lý Tự Trong junction]. On the site of the current Town Hall of Saigon, there was a canal which ran through a culvert called the Cống Cầu Dầu (“Oil bridge culvert”).

The riverside area of Saigon was covered with houses on stilts. At the lower end of rue Catinat, at the current Thủ Thiêm wharf [immediately opposite the modern Majestic Hotel], there was a Thủy các (Royal water palace) or Lữ Ông Tạ, a royal bath house built on floating bamboo rafts. They called this place Bến Ngự (Kompong Luong in Khmer), or “Royal Wharf.”

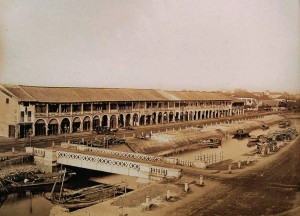

From the mouth of the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè Creek] to the point of the rue de la Citadelle [now Tôn Đức Thắng street] was the Shipyard, and opposite it the naval port.

An 1880 photograph of the Canal du Marché de Saigon or “Grand Canal,” which ran along the path of the present-day Nguyễn Huệ boulevard

A pier jutting out into the river was called Cầu Gõ or Cầu Quan. Before reaching the artillery, an arroyo called the kinh Cây Cám ran inland as far as rue d’Espagne [modern Lê Thánh Tôn street], passing the Naval Artillery and terminating at the Naval Engineering yard.

The Canal du Marché de Saigon or Kinh Chợ Vải – “Fabric Market Canal [aka the “Grand Canal,” which once ran along the path of modern Nguyễn Huệ street] went as far back as the well of this name, which was located in front of the house of Monsieur Brun, the saddler.

Between the Maison Wang Taï [the forerunner of the Customs and Excise building] and the Direction du port de commerce, there was another arroyo, called the rạch Cầu Sấu (“Crocodile Bridge Canal”), which meandered inland, eventually meeting the upper section of the Kinh Chợ Vải via the canal Coffyn, named after the Lieutenant Colonel of this name who, after remaking in earth the walls of the Citadel, had a new canal dug to connect the two ends of the old canals.

This canal was later filled, and on its location today is built the great boulevard which passes the Town Hall, connecting the rue de l’Hôpital [modern Thái Văn Lung street] with the rue Mac-Mahon [modern Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa street].

The arroyo rạch Cầu Sấu or “Crocodile Bridge Canal” was so called because it was once used for breeding crocodiles that were sold for butcher’s meat. The current Direction du port de commerce is located on the spot where there was once a fort and residence for visiting envoys from the court in Huế, and where Lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần and his nephews Nguyễn Phúc Dương and Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (later Gia Long) took refuge.

This 1865 map (courtesy IPRAUS) shows all of Saigon’s inner-city canals as described by Pétrus Ký, before they were filled by the French

So what was on the other bank of the river, opposite Saigon? In the time of Gia Long, this was the Xóm Tàu Ô or “Hamlet of the Black Junks;” this place was assigned as the home of Chinese pirates, whose small sea junks were painted black. When they offered their services to Gia Long, the king received them, and installed them with him under the name of Tuần hải Đô dinh, placing them under the command of their chief, General Xiền (Tướng Quân Xiền). They were commissioned to go and supervise the coast. Those who remained were employed in caulking [sealing the undersides of] boats in the fleet of the king.

To read Part 3 of this serialisation, click here

For other articles relating to Petrus Ky, see:

“A Visit to Petrus-Ky,” from En Indo-Chine 1894-1895

Old Saigon Building of the Week – Petrus Ky Mausoleum and Memorial House, 1937

What Future for Petrus Ky’s Mausoleum and Memorial House?

Part 3

A late 19th century map of Gia Định based on the 1815 map by Trần Văn Học, with additional place names from Gia Định thành thông chí by Trịnh Hoài Đức, Đại Nam nhất thống chí by Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn and Souvenirs Historiques by Petrus Ky

In 1885, scholar Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký delivered a lecture at the Collège des Interprètes entitled Souvenirs historiques sur Saïgon et ses environs (Historical Memories of Saigon and its Environs). Published as a booklet later that same year, it provides us with one of the most important historical accounts of Saigon-Chợ Lớn in the pre-colonial period. This is the third and final instalment of the serialisation, translated into English.

To read Part 1 of this serialisation, click here

To read Part 2 of this serialisation, click here

Now let’s take a journey along the Route basse [the “Low Road” alongside the Bến Nghé Creek] to Chợ Lớn.

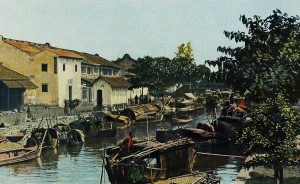

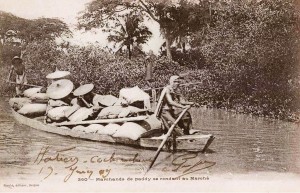

A boatman on the arroyo

The arroyo Chinois, formerly known as the Bến Nghé Creek, received its current name from the French. They observed that this arroyo led to the city of Chợ Lớn, and that its most numerous inhabitants were Chinese traders who used it to carry goods aboard their junks which moored at Xóm Chiêu (between the Fort du Sud and the Messageries maritimes), and naturally gave it the name arroyo Chinois.

According to the Gia Định thành thông chí, the name Bến Nghé derives from the fact that in times gone by, buffalo, and especially young buffalo (nghé), bathed in this arroyo.

Both banks of the arroyo have always been crowded with boats of all kinds and lined with houses on stilts, which constitute two thick ramparts, making the passage of the arroyo somewhat cramped.

In the old days, the most significant market, which enjoyed the most active trade, could be found in the area between the Signal Mast and the modern rue Mac Mahon [modern Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa street], the path of which was inhabited by fortune tellers and lathe workers. The houses around this market were well built, all of them made from fine wood with roofs covered in tiles.

From there to the Cầu Ông Lãnh Market, we pass through the territory of the ancient village of Long Hưng Thôn, comprising houses which cover the shore and stretch beyond the road. The current rue Boresse [modern Yersin street] was once a poor road, alongside which were built the dwellings of freed slaves from Laos; they made buckets from nipa palm leaves to carry water.

Arroyo Cao-Ong-Lanh, Saigon: Vue des Jonques de Mer

Over the Rạch Cầu Ông Lãnh, a small arroyo leading to the slaughterhouse, there was formerly a wooden bridge built in 1785 by a Lãnh binh or military commander [Nguyễn dynasty general Nguyễn Ngọc Thăng] who once lived in this area. This bridge – the Cầu Ông Lãnh or “Commander’s Bridge” [located close to the modern Nguyễn Thái Học and Võ Văn Kiệt junction] – gave its name to the whole quarter.

Further along, we find a bridge named Cầu Muối (“Salt Bridge”), because in days gone by, merchants in small seagoing boats (ghe cửa) would come here to sell salt. These salt sellers could still be found here long after the fall of Saigon, with their vats of salt covered with leaves. This was the largest salt depot in the city.

Advancing further, we come to the bridge named Cầu Kho and a little further on another bridge called Cầu Bà Tiệm. The area between these two bridges was the location of the Chợ Kho (“Stores Market”), so named because it was originally the location of the Royal Stores (Kho Cẩm Thảo) which King Gia Long built to accommodate taxes in kind from merchants arriving from the interior of Cochinchina. The village in which it was located was known as Tân Triêm Phường.

Continuing from the Bà Tiệm Bridge to the bridge named Cầu Bà Đô, we pass the villages of Hòa Thạnh and Tân Thạnh, popularly known as Xóm Lá (after the trade in parchment made from leaves which was carried out on the other side of the arroyo) and Xóm Cốm (after the local speciality grilled rice cakes).

A close-up of the 1815 map showing Bến Nghé (Saigon) and Tai Ngon/Saigon (Chợ Lớn)

After the Bà Đô Bridge, we arrive at the village of Bình Yên. In the old days, many of the residents here occupied large plots of land and carried out commercial exchange with merchant junk owners coming from the north.

Next we come to the bridge known as Cầu Hộc, which takes its name from an ancient well known as the Giếng Hộc which originally had a rectangular wooden interior frame to measure the water level [Hộc meaning “measure of capacity”]. Today we can still find a well at this spot containing clear and potable water which is especially good for making tea.

From this arroyo to the stream near Chợ Quán Hospital (Lò Rèn Thợ Vắp) was once the territory of the ancient village of Tân Kiểng.

Chợ Quán Hospital is located in the territory of Phú Hội Thôn, which used to have many lime kilns. Beyond the hospital we cross a bridge and continue to the villages of Đức Lập and then Tân Châu, popularly known as Xóm Câu (“Fishing Hamlet”).

A little further on is the village of An Bình Thôn, popularly known as Xóm Dầu (“Oil Hamlet”) and centred on the Rạch Xóm Dầu, a waterway where dredging ships are moored today. There was an oil depot here which specialised in the production of peanut oil.

As we continue through An Bình Thôn, from the Rạch Xóm Dầu to the pont de l’Usine à décortiquer (Bridge of the Rice-Husking Factory), we notice that part of An Bình Thôn lay on the other side of the arroyo Chinois. Today it is known as An Hòa village, and we can find there the Vạn Đò or Pagode de l’Association des Bateaux de passage (Pagoda of the Association of Transit Boats).

Inside a Chợ Lớn rice husking factory

Just before the Bridge of the Rice-Husking Factory there is an arroyo with a beautiful bridge named the Rach Bà Tịnh which still survives to this day. This waterway penetrates deep into the interior, reaching as far as the great tamarinds on the Route haute (High Road).

A little further on we reach the Adran Well. This once stood on the bank of the arroyo, but thanks to the action of water of the Vịnh Bà Thuông over a long period of time, the land on which it stands now extends out in the arroyo. Many rice husking factories have been set up here on the banks of the waterway.

From here, the village of An Điền stretched as far as the iron bridge formerly known as the Cầu Kinh. This area was known by the popular name of Xóm Chỉ (“Thread Hamlet”), after its main product. It was here that an arroyo once connected the Rạch Bến Nghé with the Ngã Tư Market, passing through the Rạch Lò Gốm. The Bà Thuông Canal, which today runs from Chợ Lớn to Ngã Tư, was dug by Viceroy Lê Văn Duyệt, the “Great Eunuch.”

On the other side of the arroyo Bến Nghé, parallel to the bank we have just travelled along, were a number of other settlements. Stretching from the Messageries maritimes to the Rạch Ông Lớn were the villages of Khánh Hội, Tân Vĩnh and Vĩnh Khánh; between the Rạch Ông Lớn and the Rạch Ông Nhỏ were Bình Xuyên and Tứ Xuân, popularly known as Xóm Te; and west of the Rạch Ông Nhỏ were An Thành (today Tuy Thành), Bình Hòa (Thạnh Bình, popularly Xóm Rớ), An Hòa Đông and Hưng Phú (Xóm Than).

A close up of the 1815 map showing the area immediately west of the 1790 Citadel

A row of houses, mostly huts on stilts, border the banks as far as Chợ Lớn. The two banks of the arroyo are also lined with boats from different provinces. The middle of the arroyo is continually crossed by small boats (ghe lườn) whose owners sell cakes, food and supplies of all kinds. Watching these boats travelling back and forward is like watching the to-and-fro of the yarn on a knitting machine!

Now, let’s follow the Route haute (High Road) from Saigon to Chợ Lớn [today Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai and Trần Phú streets]. The French government has preserved this ancient road, widening and paving it. It was originally traced by M Ollivier, the man responsible in 1790 for the construction of the Citadel, in order to create a direct route between Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

Families were given three ligatures and a piece of cotton cloth for each tomb that had to be removed during the construction of the road. On both sides of the road, mango and jackfruit trees were planted alternately, in long rows.

At the right corner of the ancient Citadel (the location of the old Palais de justice) there was a sulphur depot (Trường Diêm), while on the location of the new Palais de justice, one could originally find the Xóm Vườn Mít (“Jackfruit Garden Hamlet”) or Xóm Bột Vườn Mít (“Flower and Jackfruit Garden Hamlet”). So it seems that there was once a jackfruit plantation at this location, and its inhabitants also manufactured and sold flour.

Later, in the area occupied by the Maison Centrale (Prison) and the new Palais de justice, there was a market called Chợ Cây Đa Còm (“Curved Banyan Tree Market”), clustered around a huge banyan tree with a bent trunk.

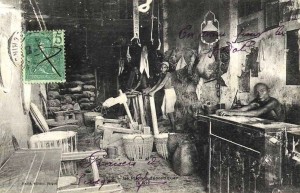

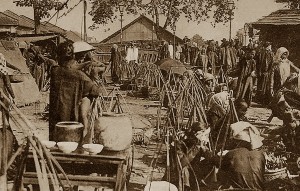

A Saigon market scene

Besides the food which was sold there, a row of shops had displays of drums, umbrellas, saddles and graduation caps for those who had passed the mandarin examinations.

After this market, also on the north side of the street, was the old Chợ Đũi (Raw Silk Market), where the city’s silk trade was based. A little further on, before reaching the route de Thuận Kiều [modern Cách mạng Tháng 8 street], was Xóm Đệm Buồm, the district which specialised in mats and sails. Today, the name of Chợ Đũi applies to the entire upper part of the rue Boresse up to and around the railway line [now the area around the Phù Đổng six-way junction].

On the way along the route de Thuận Kiều up to the Stud Farm, one passes the Cây Đa Thằng Mọi or Điều Khiển Market: Cây Đa Thằng Mọi means “Banyan tree of the slaves,” while Điều Khiển was the title of a military intendant. The market was built and opened by an intendant, hence its name.

But why the name: “Banian tree of the slaves?” It came from the goods that were traded in this market. It specialised a popular type of terracotta candlestick which was shaped to look like a black slave, with a lantern fixed to its head, in the bowl of which one immersed a wick in peanut or coconut oil.

This market, which extended from the front of the Maison Blancsubé [the grand residence of Jules Blancsubé, mayor of Saigon from 1879-1880, on what later became route Blancsubé, modern Cống Quỳnh street] up as far as the railway line, was filled with houses and shops.

![L0055713 Cochin China [Vietnam].](https://www.historicvietnam.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Plaine-des-tombeaux-by-John-Thomson-1867-Wellcome-Library-London.-Wellcome-Images-300x218.jpg)

The Plaine des tombeaux by John Thomson, 1867 (Wellcome Library, London, Wellcome Images)

Near the Stud, we see the Kim Chương Pagoda, built during the reign of Gia Long on the site of an ancient Cambodian sanctuary. It became famous as a result of two gloomy events which took place there, yet both remain shrouded in mystery.

During the war, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần (Duệ Tông), uncle of King Gia Long, and Prince Nguyễn Phúc Dương (Mục Vương) fell into the hands of Tay Sơn – the first at Bassac (Cà Mau) in 1776, the second shortly afterwards at Ba Vát (formerly in Vĩnh Long province, now in the district of Bến Tre, northeast of Mỏ Cày – and both of them are said to have been executed in this pagoda in 1776.

The Camp des Mares [located in the area south of the modern Công Quỳnh-Phạm Viết Chánh junction], where today you can find the barracks of the Annamite riflemen, was once the Hiển Trung tự (Temple of Brilliant Loyalty) or the Miếu Công thần (Temple of Meritorious Officials). Built by order of Gia Long, it was dedicated to the memory of former royal servants to which the government, at fixed times, solemnly made offerings and sacrifices.

The pagoda contained inscribed tablets for every man of merit who had served the state well. Those of several Frenchmen who died serving Gia Long could also be found here.

Environs de Saigon – Habitations de pêcheurs

Another pagoda, now occupied by the officers of the Annamite sharpshooters, was situated in front of the perimeter wall and flanked by two ponds planted with water lilies, which spread their perfume across the royal road. This was also built in the time of Gia Long, and was known by the names Miếu Hội Đồng or Miếu Thính.

In the old days, two brick columns – one at each end of the section of road running past these two pagodas – contained signs inscribed with the words: Khuynh cái, hạ mã (“Remove hat and dismount”).

Continuing past the Ferme expérimentale des Mares [an experimental farm on the same siter belonging to the Jardin botanique et zoologique de Saïgon] to the route Stratégique, the road once passed a pagoda named Chùa Ông Phúc or Chùa Phật Lớn, now demolished.

After passing a stream linked to the source of the Rạch Cầu Ba Đô, you would have seen the tombs of two princes, Hoàng Thùy and Hoàng Trớt, who it is said were the sons of Nguyễn Văn Nhạc [Tây Sơn king Thái Đức, 1778-1793]; at this location there was once a market called Chợ Mai (“Morning Market”).

Opposite the avenue de l’Église de Chợ Quán [modern Trần Bình Trọng street], on the plain, there once stood the Kim Tiên Pagoda, on the foundations of which we built another temple named the Nhơn Sơn Tự.

On the avenue de l’Hôpital, there was once another pagoda called the Gia Điền Pagoda, which no longer exists today.

A Chợ Lớn market scene

As we advance towards Chợ Lớn, we first come to the village of Xóm Bột, where flour was made and sold on both sides of the road. After passing through this village, we arrive at market Chợ Hôm (Evening Market).

Behind this market one can still find the Trần Tướng Pagoda, which was built by King Gia Long in honour of one of his mandarins who was killed by the Tây Sơn.

On a small arroyo where the pagodas of Chinese cemetery are located, there was a small bridge called Cầu Linh Yển. According to tradition, a soldier named Yển carried Gia Long on his shoulders when he was fleeing his Tây Sơn pursuers. At this bridge, he was replaced by another soldier. Exhausted, Yển stopped to rest; however, the Tây Sơn arrived and put him to death. Gia Long built a pagoda in this place devoted to his memory. The village was called Tân Thuận or Hàm Luông.

Here, under the shade of a large tamarind tree, were several quán (hostels) called Quán Bánh Nghệ. From here to the rue des Marins [Trần Hưng Đạo B street], the agglomeration of houses formed part of Xóm Chỉ.

Now let’s walk through ancient Chợ Lớn, before returning to Saigon looking at places on the south side of the Route haute (High Road).

The original Chợ Lớn (“Big Market”) was located on the site of today’s Chợ Rẫy.

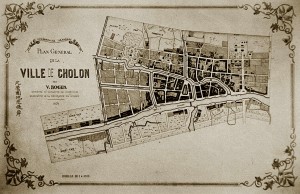

An 1874 map of Chợ Lớn

The area between the rue des Marins [Trần Hưng Đạo street] and the arroyo de Chợ Lớn was inhabited by the Minh Hương, a mixed race Chinese people who wore Vietnamese dress and lived in a village which was granted privileged status by the king.

The arroyo de Chợ Lớn was lined with brick-built shops called Tàu Khậu which were leased to Chinese traders who came from China once every year on sea junks. They brought their goods into these stores where they sold them either wholesale or retail during their stay in Saigon.

The bridge that led across this arroyo [now Hải Thượng Lãn Ông street] to the current city market [on the site of the modern Chợ Lớn Post Office] was called the Cầu Đường (“Sugar Bridge”), because the traders around it sold candies in tablet form and in jars.

The edges of the canal which passed in front of the house of the Đốc Phủ of Chợ Lớn [Đỗ Hữu Phương, 1840-1914, Governor of Chợ Lờn province] formed the rue de Phố Xếp [now Châu Văn Liêm street], while the bridge which crossed this canal carrying the route de Cây Mai [modern Nguyễn Trãi] was named Cầu Phố.

The angle formed by the canals from the market up to the iron bridge contained the Quới Đước village and the Chợ Kinh Market.

Cochinchine 1903 – Cholon, canaux intérieurs

The arroyo de Chợ Lớn, stretching westward from the pont du marché (Cầu Đường) to the Cầu Khâm Sai and to the Lò Gốm Creek, was lined with houses.

The Lò Rèn Market, located on the site of the present church in Chợ Lớn [the earlier St-Michel Church on upper rue de Paris, now Phùng Hưng street], was inhabited by blacksmiths and manufacturers of iron wire, who lived in the Xóm Mậu Tài.

Going northward to Cây Mai Pagoda, one crossed the Cầu Ông Tiều bridge.

The Cây Mai Pagoda was originally a Cambodian sanctuary, surrounded on all sides by ponds, in which an annual regatta was held in honour of the Buddha. This pagoda was restored by the Annamites. During the reign of Minh Mạng, General Nguyễn Tri Phương, who came to Cochinchina with mandarin Phan Thanh Giản, endowed it with a two storey building. The name of the pagoda and the hill on which it stands comes from the apricot trees growing there, whose white flowers are highly valued by the Chinese and Annamites.

The current Inspection de Chợ Lớn stands on the site once occupied by the Tân Long District office and administrator’s residence.

Now let’s retrace our steps and head back to Chợ Quán.

The name of Chợ Quán, also applied to the villages of Tân Kiềng, Nhợn Giang, Bình Yên, was originally that of the market located under the big tamarind trees of the avenue de l’Hôpital de Cho-quan. There were many hostels here, hence the name Chợ (market) Quán (auberge or hostel).

An 1889 drawing of Petrus Ky’s house in Chợ Quán

Between the avenue de l’Hôpital and the Experimental Farm of the Camp des Mares was the so-called “village of the founders,” Nhơn Ngãi (today Nhơn Giang). In this area we can still find the remains of an ancient Cambodian village. A large Cambodian pagoda with brick towers once stood here. Excavations unearthed Cambodian bricks, terracotta water lilies, and small Buddha statues made from bronze and stone. Two blocks of highly polished granite decorated with relief sculptures may still be seen there today.

Today, the area around the road which descends from Chợ Quán (Nhơn Giang) to Cầu Kho is dotted with houses surrounded by gardens. In the time of Gia Long, the first section of this road as far as the Maison Blancsubé was populated by miserable beggars. Seeing the arrival of the Tây Sơn in pursuit of King Gia Long, they gathered on the street and beat drums, making a terrible din. The Tây Sơn army stopped, figuring that they had encountered a serious obstacle which needed to be overcome, and Gia Long escaped. Later, Gia Long built houses to accommodate these beggars in reward for the services they had rendered him on this occasion.

This hamlet was named Tân Lộc Phường. The bridge over the arroyo behind the Maison Blancsubé was called Cầu Gạo (“Rice Bridge”), because this is where rice was sold. Long ago, Cambodians grew rice in this place, and also made mats.

Merchant boats on the banks of an arroyo

In front of the Maison Spooner, they sold sheets of white leaf parchment, lá buôn, and an agglomeration of dwellings made up the Xóm Lá Buôn.

From there to the prison, we see by the roadside several country houses belonging to government mandarins and officials. At the top of the rue Boresse was the Cầu Quan (“Mandarins’ Bridge”).

Today, as we take rue Mac-Mahon [modern Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa street] up to the rue des Moïs, we pass the new Palais de justice, the Palais du gouvernement and the Collège Chasseloup-Laubat, which are all located outside the area of the ancient Citadel. In the time of the “Great Eunuch,” this area contained the residence of Lê Văn Duyệt’s wife (Dinh Bà Lớn), the lodge of the Viceroy (Nhà Hoa), the theatre (Nhà Hát) and the archery range (Trường Ná).

Next to the house of M de Lanneau, one can still see two casuarinas; this area once housed the Nền Xã Tắc – a sacred platform where sacrifices were made to the gods. The city park was previously the village of Xóm Lụa (“Silk Hamlet”), where silk was bleached, sewn and sold.

On the Route stratégique which leads up to the Stud, one passes the villages of Xóm Thuẫn (“Cakes Hamlet”), Xóm Chậu (“Pottery’ Hamlet”) and Xóm Củ Cải (“Turnip Hamlet”).

Let’s turn right now and follow the rue des Moïs [modern Nguyễn Đình Chiểu street] eastward, until we reach the second pont de l’Avalanche. As we travel along this road, we notice on our right, across from M Potteaux’s residence, the former Saigon prison, and a bit further on, the former Elephant Park and the market named Chợ Vông, located between the cemetery and the second pont de l’Avalanche.

A close up of the 1815 map showing the area east of the 1790 Citadel

In the area between the third pont de l’Avalanche, the Cầu Xóm Kiều (now Tân Định) and the Chợ Xã Tài market, there was once a large village which contained as many as 72 pagodas.

Now let’s travel down from the second pont de l’Avalanche to the mouth of the arroyo de l’Avalanche.

The second bridge was originally known as the Cầu Cao Mên (Cambodian Bridge); but we gave it the new name Cầu Hoa. However, since the word Hoa was forbidden out of respect because it was used by princes of royal blood, the bridge was subsequently renamed Cầu Bông.

The arroyo called the Tắt Cầu Sơn was crossed by two bridges, the first called the Cầu Sơn (“Lacquer Bridge”) and the second Cầu Lầu (“High Covered Bridge”). As for the name Thị Nghè or Bà Nghè, given to both the first bridge and the arroyo de l’Avalanche itself, here’s the story:

Nguyễn Thị Khánh, the daughter of senior mandarin Vân Trường Hầu, was married to a scholar employed in the provincial administration with the title Ông Nghè (bachelor or graduate). To facilitate the crossing of the arroyo for her husband as he travelled back and forwards every day to his office, she had a bridge built, which was named in her honour Thị Nghè or Bà Nghè, “Madame bachelor.” The arroyo was given the same name.

Marchands de paddy se rendant au Marché

In front of the Hospital of the Sisters of Sainte-Enfance at Thị Nghè, there was a rice field reserved especially for the annual royal event known as the Tịch Điền (ploughing) ceremony. Next to it was a platform reserved for sacrifices to Thần Nông, also known as Chinese Emperor Shennong, who invented the first agricultural implements and is worshipped as the god of agriculture.

Between this area and the bank of the Saigon River above the arroyo de l’Avalanche, there was the Văn Thánh Miếu, a large temple dedicated to the worship of Confucius.

When we compare this journey through ancient Saigon and its environs with a trip through the modern city, we can see the rapid physical changes that Saigon has experienced over the years, helping us to reflect on the instability of human affairs.

Thanks to the activities of the French, a country which was almost ignored for the last century, organised in villages which later became the residences of kings and provisional capitals, has now been cleaned and embellished to become the capital of six provinces and one of most beautiful cities in the Far East.

NOTE

It is not without interest to portray in passing the character of Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt, a man so adroit as a minister, so energetic as a general, and so skilful and severe as an administrator.

Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt

In 1799, it was thanks to the energy, stubbornness, and cold determination of the Envoy of the Palace Left Guard and General of the Pacification of the Tây Sơn that a famous victory, dearly bought, however, was obtained at the port of Thị Nại (Quy Nhơn).

The first edict of prohibition against the Catholic religion and Europeans in general, ordering the demolition of churches, was launched in 1828 by Minh Mạng.

The Viceroy was attending a cockfight when news of the decree of persecution reached him. “How,” he cried, “can we persecute the fellow believers of the Bishop of Adran, and the French, whose rice we still chew between our teeth? No,” he added, ripping up the royal edict in indignation, “while I live, we will not do this, let the King do what he wants after my death.”

He was severe in the administration of Lower Cochinchina. He was also the terror of the Cambodians and Cochinchinese. His power to condemn people to death and carry out the sentence before sending a report to the king and the minister of justice was the power which kept the peace throughout his rule.

One day, going to Chợ Lớn, he observed on the side of the route de Cầu Kho a child aged four or five years, cursing and disobeying his father and mother. He wanted to stop to chastise the child, but changing his mind, he continued his journey. That evening, on his way back along the same road, he heard the child again, uttering insults and curses against his parents over the dinner table. He stopped and asked the parents for permission to remove the child. Then he gave him food and ordered him to eat with a pair of chopsticks which were purposely given to him the wrong way round. The child turned the chopsticks round to their correct position and began to eat. The governor then seized and beheaded the child immediately, saying that he clearly had enough intelligence to understand the enormity of the crime he had committed.

Saigon – procession annamite

On another occasion, when leaving the city, the Viceroy saw a thief running away after stealing a roll of cigarette paper. He had him caught and beheaded on the spot, without any form of judgment.

He considered it his duty to govern Cochinchina by excessive severity and rigour in the application of laws against crimes.

The first example he gave of his ruthless provisions was the execution of one of his scribes (Thợ lại). Coming out of the office one day, this man met a vendor of soups or sweets at the gate of the Citadel. Wanting to amuse himself, he put his hand on the betel box that the merchant had placed on the lid of his basket, but the vendor cried “Thief!” Caught in the act, the scribe was beheaded immediately on the orders of Lê Văn Duyệt, without any judicial proceedings. Soon, the report of this summary judgment struck terror throughout Cochinchina.

To be respected and feared by the Cambodians, he went to Udong in the capacity of an Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Envoy. Sitting on an elevated platform next to the King of Cambodia, he was eating candy (đường phèn) and drinking tea. Hearing his teeth crack as he chewed the sugar cubes, some Cambodian courtiers asked the Annamite officers present at the reception what the Tướng Trời (“Celestial General”) was eating. The latter replied that he was eating stones and pebbles.

As Cambodia was under the protectorate of Annam, the king of this country was obliged to come to Saigon every year at Tết (New Year) to pay his respects to the king of Annam in the Royal Pagoda, together with the Viceroy.

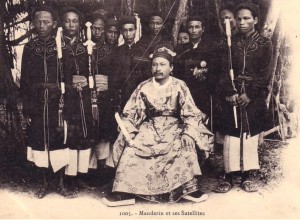

Mandarin et ses Satellites

On one occasion, the Cambodian king, accompanied by the officer in charge of the protectorate, arrived on New Year’s Eve; but instead of going to Saigon, he spent the night in Chợ Lớn. Early next morning, the Viceroy proceeded with the ceremony without waiting for the king, who did not arrive until after it was already over. He was subsequently condemned without mercy and forced to pay a fine of 3,000 francs before returning to Cambodia.

Lê Văn Duyệt had a passionate love for cockfighting, comedy and theatre. He maintained his own theatre troupe and had his own theatre. Buildings used for all these diversions were located outside the walls of the ancient Citadel, on land now occupied the Palais du gouvernement and the Collège Chasseloup-Laubat.

The Annamites say that this great Tả Quân had something majestic in his person, and especially in his eyes.

It is said that the tigers he raised for combat were afraid of him and obeyed his voice. Even the most indomitable elephants feared the Viceroy. The biggest and the baddest, called Voi Vinh, was subject to fits of rage, during which he rampaged around, picking up and tossing aside everything that was in his path. When he heard about this, the Viceroy rode in on his palanquin and, standing directly in front of this huge animal, called him by his name and ordered him to calm down. The animal, as if he understood, calmed down immediately.

Finally, I will mention just a few renowned historical and monumental tombs on the Plaine des tombeaux.

A mandarin’s tomb

Everyone knows the tomb which stands next to the tramway line near the Maison Vandelet. This tomb was built by Minh Mạng in honour of his father-in-law, Huỳnh Công Lý, who was beheaded by order of the Viceroy Lê Văn Duyệt. Huỳnh Công Lý was the Phó Tổng Trấn (Deputy Governor) of Gia Định (Saigon). However, in 1821, when the Viceroy went on a trip to Huế, Lý had illicit relations with one of the latter’s women. After returning from the capital, the Viceroy was informed of the behaviour of his subordinate, and had him executed immediately and without any regard for Minh Mạng .

The great tomb that one sees next to that of the bishop of Adran is that of Tả Dinh, brother of the Viceroy Lê Văn Duyệt, who died before him.

For other articles relating to Petrus Ky, see:

“A Visit to Petrus-Ky,” from En Indo-Chine 1894-1895

Old Saigon Building of the Week – Petrus Ky Mausoleum and Memorial House, 1937

What Future for Petrus Ky’s Mausoleum and Memorial House?

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

https://www.historicvietnam.com/historic-memories-3/